Henry Olsen’s book The Working Class Republican shows how the party of Reagan can once again stand for the forgotten man.

The foreign eye can discern peculiarities of national character that often go unnoticed by natives. A few years back, a writer in the British magazine The Economist noted Americans’ deep appreciation for the nobility of work and said that “in America they call waiters sir.” More than a century before, Alexis de Tocqueville observed Americans’ passion for upward mobility: “The first thing that strikes one in the United States is the innumerable crowd of those striving to escape from their original social condition.”

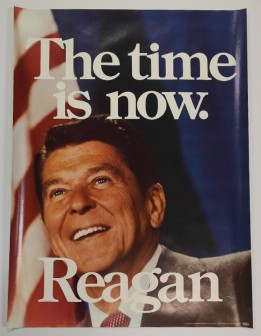

One of the stranger features of today’s political environment is how much of the governing class either condescends to blue-collar workers or treats them with something bordering on derision. Few political leaders express an ethic of respect for and insistence on labor. It was not always so. “All must share,” Ronald Reagan once declared, in both the “productive work” and the “bounty of a revived economy.”

At a time when it is fashionable to assert that there are “jobs Americans won’t do” and to denigrate American workers who have no income-tax liability, Reagan’s words have a profound resonance:

“Those who say that we’re in a time when there are not heroes, they just don’t know where to look. You can see heroes every day going in and out of factory gates. Others … produce enough food to feed all of us and then the world beyond. You meet heroes across a counter, and they’re on both sides of that counter. … Their patriotism is quiet, but deep. Their values sustain our national life.”

For many who remember Reagan as a supply-side fundamentalist, it’s a matter of incredulity that he might have spoken in this way. By instinct or by intention, his defenders and detractors by and large agree that the 40th president was nothing if not a libertarian stalwart stirred by opposition to the Leviathan above all else. In the popular imagination, his economic preferences entailed tearing down the modern welfare state just as surely as he sought the destruction of the Berlin Wall. This narrative is worth dwelling on for several reasons.

First, it is ahistorical nonsense. The conception of Reagan as a partisan of the minimalist “night watchman state” in which the only legitimate functions of government are to guard the coasts and deliver the mail has little basis in fact. What’s more, in the light of Reagan’s canonical status among the conservative pantheon, this misconception regularly leads the right astray. It encourages the adoption of an abstract, doctrinaire philosophy that ignores the country’s most pressing problems.

In The Working Class Republican, Henry Olsen furnishes a withering critique of this dogma about the most successful president of the last half-century. A conservative policy analyst with the Ethics and Public Policy Center in Washington, D.C., Olsen places Reagan squarely in “the public New Deal” tradition of energetic government support for the “forgotten American.”

This revisionist thesis amounts to a frontal assault on the conservative shibboleth that Reagan picked up where Barry Goldwater left off. Goldwater’s ill-fated presidential campaign is usually hailed on the right as an indispensable dress rehearsal for the Reagan revolution. (In George Will’s memorable observation, Goldwater “won the election of 1964; it just took 16 years to count the votes.”) Olsen pours cold water on this pious myth, positing that in his hyperindividualism Goldwater was more Reagan’s foil than his forerunner.

The argument that Reagan was a champion of the value and dignity of the average individual first and foremost – and that this identity was critical to his political success – is liable to invite shock or dismay among those accustomed to viewing Reagan as a Tea Partier avant la lettre. But Olsen marshals a compelling case that, contrary to certain convenient myths on the left and right, Reagan meant it when he said that he was a New Deal Democrat – who voted for FDR four times – until the party abandoned him. What made Reagan a Democrat at the onset of his political consciousness was his conviction that federal action could “place a floor under every American’s standard of living without placing a ceiling above those who sought more.” It was a conviction that would prove his political North Star.

This is not to deny that Reagan was suspicious of overweening government power. To the contrary, he was fiercely opposed to technocratic schemes that aimed to reshape man and society. This progressive approach threatened to fundamentally transform the citizen’s relationship to the state, and Reagan had no time for it. But he was not against using government to enhance human capital in ways that would equip people to live more freely. His abiding view was that, in Olsen’s words, “government – preferably state or local, but federal if necessary – should give people in need a hand up to help them pursue their dreams.” This was not a recipe dependency, but for nurturing the individual in his pursuit of happiness.

If Reagan’s formula was so potent, one might ask why Republicans, who generally hold his greatness to be an article of faith, have not been able to repeat his success of late. Indeed, Republicans have only narrowly been spared further confinement in the political wilderness thanks to an incompetent narcissist with open contempt for the conservative creed they purport to hold dear.

Olsen’s answer is as simple as it is sobering: “Today’s conservatives fundamentally misunderstand Reagan’s legacy.” This applies to conservatives of establishment and populist stripes, and Olsen spells out exactly where they go wrong: “They remain unreconciled to the New Deal’s core principle: the primacy of human dignity sanctions government help for those who need it.”

To recall Reagan’s authentic record is to understand what has gone wrong with the American right. Reagan’s New Deal-inflected conservatism has become something of a dormant political tradition. In contrast with Reagan’s peculiar synthesis of conservative and liberal philosophies, Republican sensibilities now recoil in agony at the notion that the era of big government isn’t over, and won’t be anytime soon. This did not trouble Reagan, who was always more concerned, writes Olsen, “with what government ought to do than the fact that government was used to do it.”

It’s a great shame that “The Working Class Republican” wasn’t on hand nearly a decade ago when the response of Republicans’ ideological enforcers in the midst of the worst economic distress since the Great Depression was to double down on a commitment to dismantling the New Deal settlement. Instead of responding to the recession by taking seriously the threat of premature austerity to economic growth, Republicans fixated on the debt as a threat to future prosperity. (The recklessness of this approach was on full display when congressional Republicans engaged in brinksmanship over the arbitrary debt ceiling with the chief effect of downgrading America’s credit rating.)

Over the course of the last decade, it has been increasingly clear that the true lodestar of today’s Republican Party has not been Reagan but Barry Goldwater. Examine modern Republican attitudes and you are immediately confronted with an essentially negative program, not so much pro-right as anti-left. This can be traced back to the GOP’s 1964 candidate for president. (“I do not undertake to promote welfare, for I propose to extend freedom,” said Goldwater. “My aim is not to pass laws, but to repeal them.”)

A great deal of Republicans’ shrill and needlessly chafing rhetoric about the role of government comes, like anti-Semitism, on the edge of a remark. Contemporary Republican politicians tend to call for “small government” rather than a more prudent and realistic “limited government.” Republicans today may reluctantly defend the “safety net,” but Reagan extolled the “social safety net” – a small but significant distinction that conveys a sense of obligation to the less fortunate in society. Rather than Reagan’s odes to the modest but heroic working man and woman, too many Republicans have fallen into the habit of scoffing at much of America’s labor force as “takers.”

This has created a widespread impression that Republicans and conservatives care more about donning green eyeshades than ensuring all citizens are fit for lives of ordered liberty. Put differently, they often seem more concerned about saving money than enhancing life. In its zeal to pare down the state, the right has forgotten (as Reagan never did) Lincoln’s assertion that their party is “for both the man and the dollar; but in cases of conflict, the man before the dollar.”

This urge to overturn the vast American welfare state helps account for the dismal fact that the Republican presidential nominee has failed to win a majority of the popular vote in six of the last seven elections. Since Reagan left office, as was said of the Bourbons of France, the self-styled True Conservatives have learned nothing and forgot nothing. This is a travesty because, as Reagan said in 1977, principles can adapt to new facts while ideologies cannot.

At a time when the GOP remains in thrall to a stale ideology that recycles Reaganite slogans while betraying its most basic principles, this is a message all conservatives need to hear. The willful ignorance of Reagan’s real legacy should be forcefully repudiated, not least by Republicans who understand that only with an affirmative agenda can they reclaim their mantle as the party of work and aspiration.

It will not be easy. Under a corrupt and corrupting president and a feckless congressional leadership, the Republican Party is in a truly wretched position. The principal initiatives of Republicans under the Trump administration thus far have been scrapping the components of Obamacare that expanded insurance coverage and lowering the top marginal tax rate – not exactly an agenda to gladden the hearts of Trump’s traditionally Democratic blue-collar voters in the Rust Belt.

We will know these false prophets of Reaganism have been replaced by its rightful heirs when the heroes across the counter are again called sir and ma’am, and treated accordingly.

A version of this review appeared in National Review.